Contra Marc Owen Jones: Blacks are not Equally as Likely to be Attacked by Whites as the Reverse

This post has a companion. Click here to read about why the reverse claim is also incoherent.

This post is a response to Marc Owen Jones's tweet (archived here) in which he claims that the rate of white on black violent incidents is similar to the rate of black on white violent incidents. The graph that he uses to support his claim was generated with incoherent reasoning. The graph is available in a BJS special report [1]. This is also a response to Rachel E. Morgan, Ph.D., BJS Statistician, who generated the report.

My alternative claim to Marc Owen Jones's claim, is that in the United States, one particular white person is 6.87 times as likely to be attacked by one particular black person as one particular black person is to be attacked by one particular white person.Jones's claim:

To evaluate the meaningfulness of Jones's claim, and the meaningfulness of the similar reverse claim, we have to have establish what observations we would expect to see if nothing were amiss: what we would expect to see if there were no disparity in any direction of rates of interracial violence. So please carefully consider the below hypothetical scenario and the below 4 claims about the hypothetical scenario.

Hypothetical Scenario: All violence is random

Consider a hypothetical town with 900 blondes and 100 redheads. In this town, 1 out of every 10 people attacks a random person.

Simple calculations determine the expected outcome: 90 blondes commit attacks; their victims are 81 blondes and 9 redheads. 10 redheads commit attacks; their victims are 9 blondes and 1 redhead.

At first it seems that blonde-on-redhead violence is in parity with redhead-on-blonde violence. Nothing is amiss in this town in terms of inter-hair violence. But consider this perspective: A redhead person is 9 times as likely to be attacked by a blonde person as a blonde person is to be attacked by a redhead person. This claim is indisputably true, but intuitively it feels like nonsense. What went wrong? It is not an incorrect claim, it is an incoherent claim.

Incoherence creeps into the claim at the ambiguity of the phrase "a person". The phrase "a person" either means "any of the persons of a group" or it means "one particular person of a group".

The claim above is only true when it is interpreted as follows:

- One particular redhead person is 9 times as likely to be attacked by any of the blonde persons as one particular blonde person is to be attacked by any of the redhead persons.

Alternative true claims are as follows:

- One particular redhead person is 9 times as likely to attack any of the blonde persons as one particular blonde person is to attack any of the redhead persons.

- One particular redhead person is equally likely to attack one particular blonde person as one particular blonde person is to attack one particular redhead person.

- Any of the redhead persons attacking any of the blonde persons is equally as likely to occur as any of the blonde persons attacking any of the redhead persons.

All four claims are correct, but claims 1 and 2 are meaningless because they are incoherent. It is clear they are incoherent because statement 1 makes the redhead people seem like victims while statement 2 makes the redhead people seem like victimizers. The claims seem to be making observations about rates of inter-hair violence, but actually they are only making observations about the minority status of redhead people.

Response to Marc Owen Jones

Marc Owen Jones makes the claim that in the United States, blacks are approximately equally as likely to be attacked by whites as whites are to be attacked by blacks. The formulation of his claim is the same as the form of claim 1 in the Hypothetical Scenario. As we have just seen, claims of this form are incoherent, and therefore meaningless.

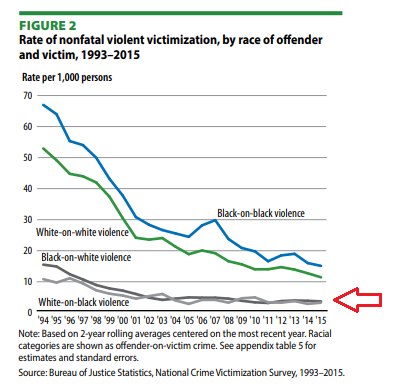

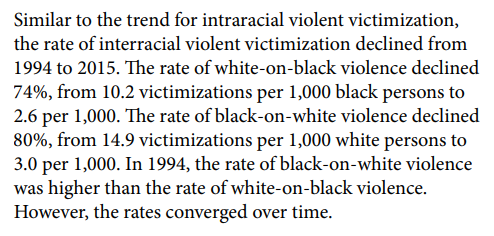

To show that Marc Owen Jones' claim is equivalent to claim 1, refer to the Special Report's explanation [1] as to how the "Black-on-white violence" and "White-on-black violence" time series were derived:

The time series are calculating "[black-on-white] victimizations per 1,000 white persons" and "[white-on-black] victimizations per 1,000 black persons". In other words, the time series are comparing the likelihood of:

"One particular white person to be attacked by any of the black persons"

to the likelihood of:

"One particular black person to be attacked by any of the white persons".

And so we see, the claim is equivalent to claim 1 in the Hypothetical Scenario, and therefore incoherent, and therefore meaningless.The real situation with interracial violence in the United States

One can easily make a claim equivalent to claim 1 in the Hypothetical Scenario, in which case it seems like white-on-black violence is comparable in magnitude to black-on-white violence in the United States. One can also easily make a claim equivalent to claim 2 in the Hypothetical Scenario, in which case it seems like black-on-white violence is orders of magnitude more severe than white-on-black violence in the United States. However, both of these aproaches are meaningless, because claims of the form of claim 1 and of the form of claim 2 are incoherent. There are about 4.6 as many white people as black people in the United States. When a black person is victimized by a crime, he does not generate 4.6 times as much victimhood as a white person. Claims of the form of claim 1 try to imply otherwise. When a black person commits a crime, he does not generate 4.6 times as much criminality as a white person. Claims of the form of claim 2 try to imply otherwise.

The real situation can be described by a claim of the form of claim 3 or a claim of the form of claim 4, as both of these kinds of claims are coherent, and therefore can be meaningful. It is easiest to make a claim of the form of claim 3. Using table 13 of the 2021 NCVS report [2] we see that there were approximated to be 480,030 black-on-white violent incidents and 69,850 white-on-black violent incidents. A simple ratio of these two quantities alone supports the following claim (equivalent to the form of claim 3 in the Hypothetical Scenario):

"One particular white person is 6.87 times as likely to be attacked by one particular black person as one particular black person is to be attacked by one particular white person in the United States."

Notes

- ^[a][b] Figure 2 of BJS Special Report October 2017 "Race and Hispanic Origin of Victims and Offenders, 2012-2015" generated by Rachel E. Morgan, Ph.D., BJS Statistician

- ^ The NCVS - National Crime Victimization Survey - collects information on non-fatal personal crimes from a sample of about 240,000 Americans. The NCVS is informative about interracial crime (excluding homicide) at the national level. The 2021 NCVS report is available here. The datasets are available for full download here.